Genesis

Back in the early 2000’s, when I was first learning how to write software, there was always one thing accompanying me on the desk next to my CRT monitor, clacky-clacky keyboard and mouse with a little rubber ball inside.

It was a book.

Not always the same book, but a book nonetheless.

These books were my lifeline.

They told me not only how things should work, but how I should think. The coding styles and principles applied in those pages defined how I should write code and what would be classed as “good”.

First, there is something about spending roughly £50 on something the thickness of a telephone directory that imbues it with a greater sense of worth and respect.

If someone had gone through all the effort to sit at their desk, write out twenty-five chapters on everything from Hello World() to memory pointers, get an editor to review it, publisher to agree to print it, be printed - in an actual real life factory, then shipped to a shop and sold in a bookstore by an actual real life person…well, the least I could do was to keep my end of the bargain and read to what it had to say.

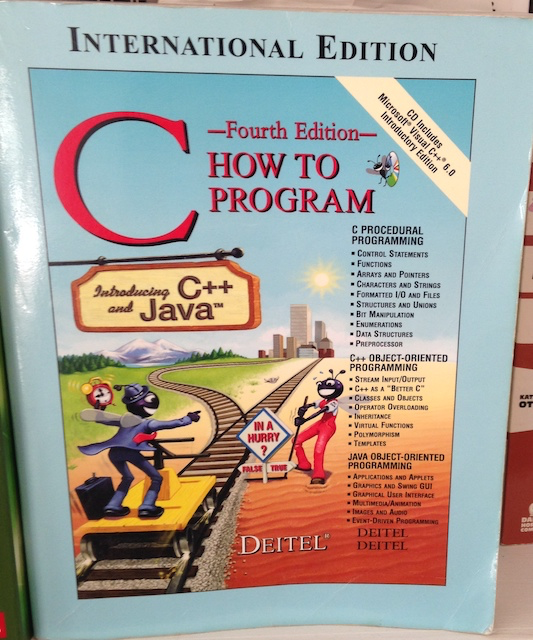

Along with the exorbitant costs associated with owning these weighty tomes, it meant that the breadth of my library was lacking. I would own a few choice books on particular topics, my pool of resources limited to what I could afford, what looked like was applicable and from the few minutes of skimming pages in Waterstones. Therefore, when it came to looking for answers on C or C++ syntax, I turned to the book with a picture of two bugs on a railway. That is not a joke, this is the cover of How To Program C (Fourth Edition):

I would look to a Deitel, or an O’Reilly, or a SAM’S for information on specific subjects and those individual books were the truth to me.

A Brave New World

It’s like when you’re a child and all you know is what your dad tells you about the world. He has an answer for everything, and that’s comforting and safe. But then you got older, new things you learn started to contradict your dad, which felt wrong and not comfortable at all, not one bit.

And so it was that the internet blossomed.

Suddenly what was unequivocal was up for discussion and those books I had referred to in order to build my own view of things became meek, fragile, old. In the blink of an eye, I didn’t have to go to bed at 8pm anymore and be told to brush my teeth…

The internet gave rise to the spirit of open source, of sharing your own work with a wider community for both collaboration and criticism. Projects could be worked on by people who had never met in person and companies would be born and flourish on the back of utilising work by strangers that had been given freely to the universe.

Websites such as StackOverflow or CodeGuru became our library whilst hosted repositories such as GitHub and BitBucket, with an infinite number of projects, became the reference section. StackOverflow to me personally provided what was incredible at the time, other developers providing answers to the most arbitrary and idiosyncratic questions imaginable. I’m getting a crash when launching an application on a specific chipset? Ah, that might be because this particular IRQ register needs to be set differently. How could I post a request to a SOAP api using cURL? How to combine two strings together in Ruby?

Answers were now everywhere. And they were all mine

Why would I want a book which would be out of date within twelve months or two years? Software tools and languages were moving at an unnatural pace, itself fuelled by the power of collaboration provided by the internet, that the book you bought an hour ago had been superseded by the time you got it back from the high street.

Such is the way of things, the books remained closed and began to gather dust.

The content within was a snapshot of an earlier time, a world of immutability. Software shipped on hardware - plastic stuff. If it had bugs or faults, tough luck I’m afraid, fingers crossed your customers get lucky and pick up the v1.1 version instead. Similarly to the software that was the product of these materials, learning resources felt that they were correct and valid forever. What use a book with wrong information?

Charlotte’s Web

Jumping forward to the present day, I have been motivated to create a style guide for my team to help keep our project consistent, help new starters and aid with reviewing pull requests.

I have an idea of what I would include in a style guide. How to handle whitespace, good naming conventions, where to use comments. But finding the right place to start and what constitutes a good guide can be hard to come by, taking into account that each organisation operates in their own different way.

But never fear. I can peruse at my leisure the Ray Wenderlich Style Guide, or LinkedIn Style Guide or even Google’s very own Style Guide.

I’m able to see how large organisations maintain their projects, what they view as important and what things take priority over other areas.

I can draw on these sets of rules and recommendations and see how they help improve a projects codebase by observing GitHub pull requests and the discussion that goes on within them.

And I haven’t had to spend £50 for any of it.

The democratising of knowledge and the willingness of both individuals and organisations to share this information can now help me to draw up my own style guide.

I can feel confident it addresses the important elements of writing code, and that I can include individual aspects that are relevant to my team and our principles.

Treasure Island

And it doesn’t end there.

I can draw inspiration (read: copy code until my arms ache) from any number of production apps who’s entire codebase is hosted publicly.

I can see how a messaging app handles a chat window by looking at Signal.

If I find an interesting behaviour or pleasing animation in the Wordpress app, I can dig through their code and see how it’s done.

And then take it.

This.

Is.

Incredible.

Years of stress and angst spent staring at a line of code wondering to myself

Is this good enough? Is this what is considered ‘production ready’?

And the answer is, without any shadow of a doubt, yes.

But that’s not the right question now, is it?

We can see first hand from any number of open sourced projects that what constitutes ‘production ready’ for that organisation does not translate to every organisation. My production ready is not yours and yours is not theirs.

But by having the resources to investigate, to dig into and understand other successful applications, it can give us the confidence to continue a train of thought or discard an implementation approach. If it works for them then it could work for us.

I like that side of open source. Not being afraid or ashamed to show how something works and opening those lines of discussion and further thought.

At the Mountains of Madness

Like me sitting alone with a family packet of Haribo, when you have unlimited resources at the ends of your arms, caution is advised.

One of the benefits of a well-researched and compiled book is that you are afforded context. Information either side of a code snippet explains why something works the way it does, to appreciate the mechanics of behaviours. Understanding that context gives us the wider knowledge to apply to a number of different situations and to aid us in our future development decisions.

Context, as a developer, is important.

Context lets us know whether we are writing something that satisfies the intended requirements and at the same time doesn’t have unexpected side effects.

Context means we write the right code.

And I’ve seen first hand what happens when you use what “kinda looks about right” without having that context.

I have had to make recruitment decisions based on coding exercises.

There have been projects I have reviewed that were good and a lot which were adequate. There were those which I can (likely unfairly) describe as “disappointing”.

The reason for that disappointment is because one of the first things I will do is to take a part of the project - normally a network or data storage function - and paste it wholesale into Google.

I would say as a conservative estimate, seven times out of ten, I’ve found the blog post or StackOverflow answer the code snippet came from. On more than one occasion, I’ve seen the same code duplicated word for word, even when the original code contains variable names or properties antithetical to the question posed to them.

For example.. make a network request and return a list of products.

I would expect to see functions or classes which constructs URLs or parses JSON.

I would not expect to see a data structure called Hotel or Room.

Unfortunately I do expect to copy that data structure into Google and find the first result is a tutorial on how to make a network request that parses JSON.

That to me is disappointing.

Not because that code was taken from another resource - it’s expected - but that the candidate didn’t want the context of why that code worked. They saw that it did what they needed, ctrl+v & ctrl+c’d, and called it a day. If I can’t see the application of intent, then I can’t take that candidate forward.

This isn’t me on my high horse, far from it. We have all taken code that kinda looks about right, when the bugs are piling up, the QA’s are tapping their fingers and the time to code freeze is ticking down.

“I just need this to work, and then I’ll go back and fix it later” we tell ourselves.

But the road to hell is paved with //Todo’s.

When it comes time to look at that code at the later date, a wrinkle will form across my brow, my eyes will dart from side to side and my hands will hover over the keyboard.

And I will write a comment.

// Warning: Not quite sure what this does

But wind back time.

Let me take that same block of code I copied earlier.

Take more time to sit and understand what it does.

Even take the opportunity to rename variables, and the future will change for the better.

That’s where context is important and the allure of the immediate response can be dangerous.

Books lend themselves to that slower reaction time and provide a natural breathing space for thoughts and ideas to take hold, to evolve, to flourish.

Wrap Up

This has been a revolution, a sea change of application and method, and we didn’t miss a step along the way. But I also think that it has become easy to take for granted these tools we have been given.

I owe my career to the advent of the internet and the willingness of strangers to share their work. Whether directly through shared code or from the software that enables me to work.

I will form a style guide, drawn from many other guides like it.

Maybe I’ll open source it and someone will use it as the basis of their own work.

Maybe they won’t.

Maybe it’ll be out of date before the day is over.

Maybe I’ll take another look at the old book on my shelf to make sure that I’m doing it right.