Introduction.

This was originally a presentation that I’d put together in early 2020 back before we entered a global pandemic.

So please imagine that we’re in a 80% full auditorium (I’m not greedy), the chairs are comfy and the host for the event has told some light hearted jokes to ease you into proceedings.

“Up next is Michael to talk about Coordinators….”

A gentle applause flutters around the room.

I walk up to the podium, looking like the kind of person who just knows what they’re talking about.

A hush settles, the lights go down and I lean towards the microphone to say…

Hello.

A word of warning, the word “Coordinator” is going to be said so many times, that it may start to lose all meaning. Which will actually help to give you a window into the pain I went through on this voyage of discovery.

In the beginning there was navigation. And it was good.

Every mobile app, website and interactive medium will involve navigating from one view to another. And handling that in a clean way can very quickly become very tricky.

About eighteen months ago, I was working on a feature and began to feel that the code to handle user flow through the app was getting a little…shall we say…“messy”.

So I looked to design patterns! There are a range of different methodologies to choose from, but I wanted to focus my attention on how to best handle navigation. I was (reasonably) happy with how I was constructing my model objects, dependencies, etc but this was one area that I felt was on the verge of becoming unmanageable. Looking into these different approaches I came across the coordinator pattern. Being able to extract navigation code into a dedicated object sounded just what I needed.

Coordinators.

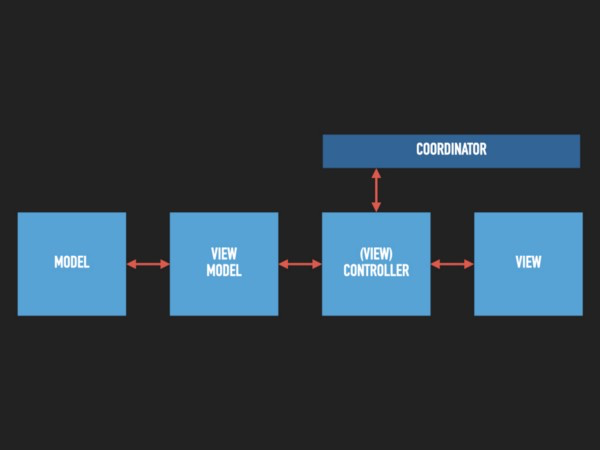

Here’s a simple representation of where the coordinator would sit in my app architecture. It’s one purpose in life — its sole reason to live — is to tell other views to either present or dismiss. All of the logic I had previously within my view controller could be moved out and dropped into something more relevant and with just one job to do.

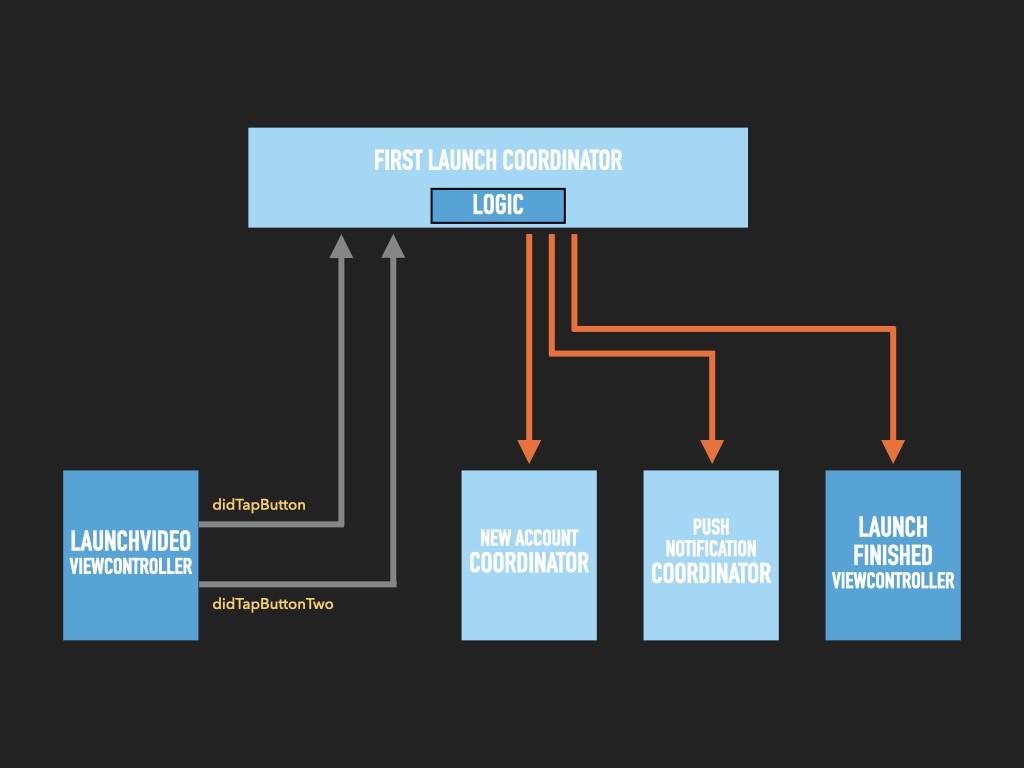

For example, I could have a coordinator which handles flow for when the app is first launched. Each controller can message back to the coordinator with which button has been tapped and the coordinator will decide which view to present next.

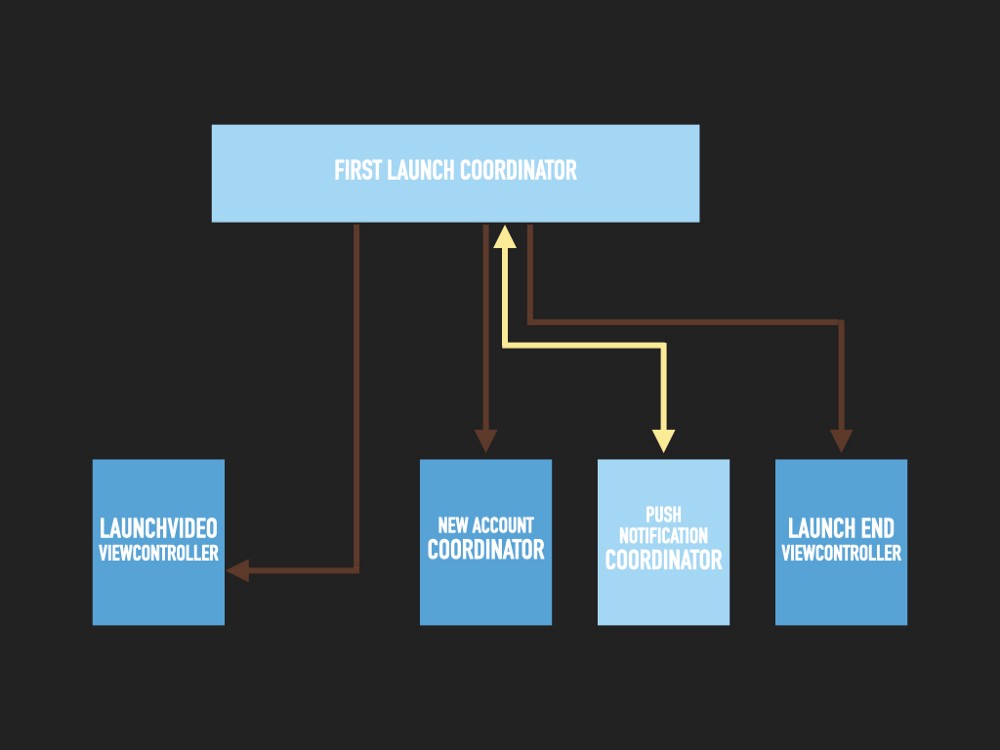

Another nice thing is that coordinators can call out to other coordinators.

Looking at our first launch coordinator, we could call out to a “new account coordinator” which begins it’s own child flow that may include things such as entering an email address, choosing a secure password or validating with a two-factor token.

This child flow is completely managed within the “new account coordinator” and, in a selfish way, the parent coordinator just doesn’t care what it does.

The only thing it does care about about is knowing when it’s done.

Kinda like when you go to a restaurant. You don’t care how they make your confit de canard, just as long as they bring it to you on a plate rather than a wooden board.

The cool thing with this is that you can have as many coordinators as you like, each calling child flows that have a focused concern on a particular part of the user journey and each of them work in isolation until they are complete.

See, coordinators are useful! It means that:

- Our view controllers can become egotistical — they neither know or care about anyone else. This reduces the amount of code they contain, helping to make our controllers more easily testable.

- The view controller interface is clearly defined. Using well-named and descriptive delegation, we can see at a glance what the intended functionality of a particular view is — does it have multiple actions? Does it just dismiss on completion?

- A coordinator defines the order of presentation. This means that if a requirement changes and we need a new view that requests consent to the hundred different tracking SDK’s we use, we can add that in just the coordinator and every other view remains unaware of where it sits within that flow.

- It also means that a coordinator can be reused within different contexts, helping to reduce code duplication.

- And finally this separation of concerns means that each individual element of our flow can be more easily tested, giving us a higher confidence that we’re doing the right thing.

Implementation.

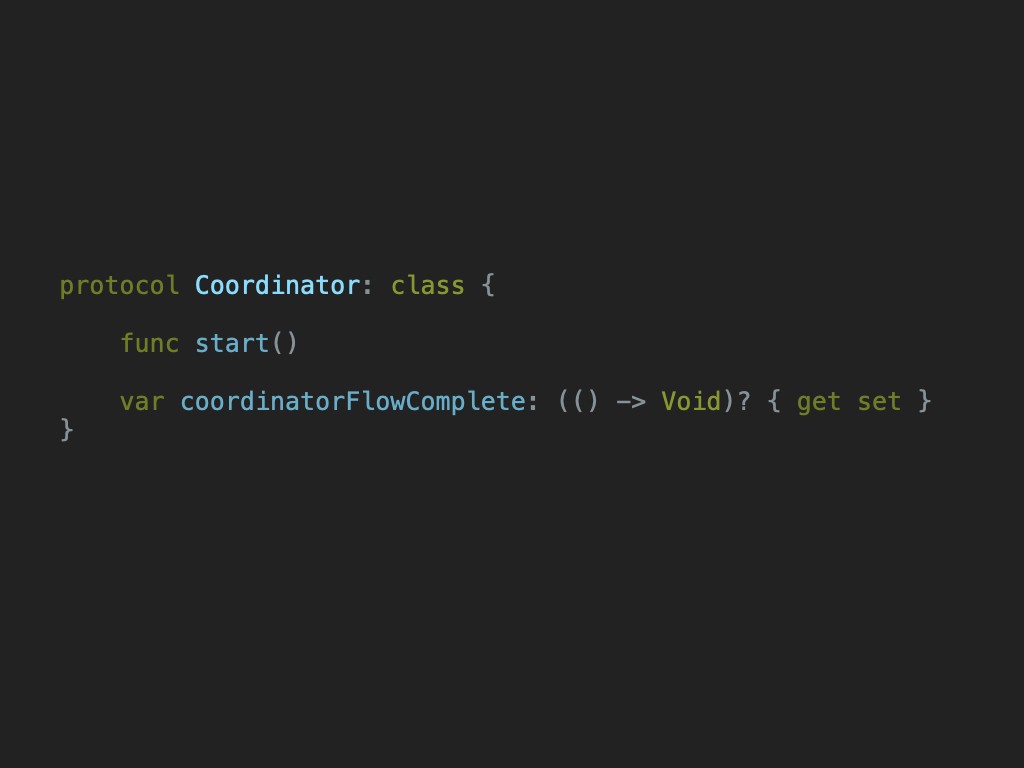

The implementation of the coordinator pattern is well documented. It hinges on a protocol with one function declaration — start.

This is the jumping off point for everything that the user flow has to do. The calling class just says “Hey, customer feedback coordinator! Start!”

And off it goes, happily presenting user input forms, confirmation windows or modal dialogues letting the user know that sorry, mismatched plates or a lack of three-ply loo roll aren’t a valid reason to demand a refund on your rented holiday home.

So what’s the problem?

Everything looks great!

Well….maybe… well, not quite.

In a lot of implementations of this pattern, the coordinator retains a collection of child coordinators.

Unfortunately, this can lead to a situation where the view is deallocated when dismissed, but with no mechanism to deallocate the coordinator.

And there is one very important question with this….

How do we deallocate a coordinator?

The simple answer to this question is…

You don’t.

And the reason you don’t?

You can’t.

Thank you and good night.

….

..

Ok, well actually that’s not quite true. There are many things you can do.

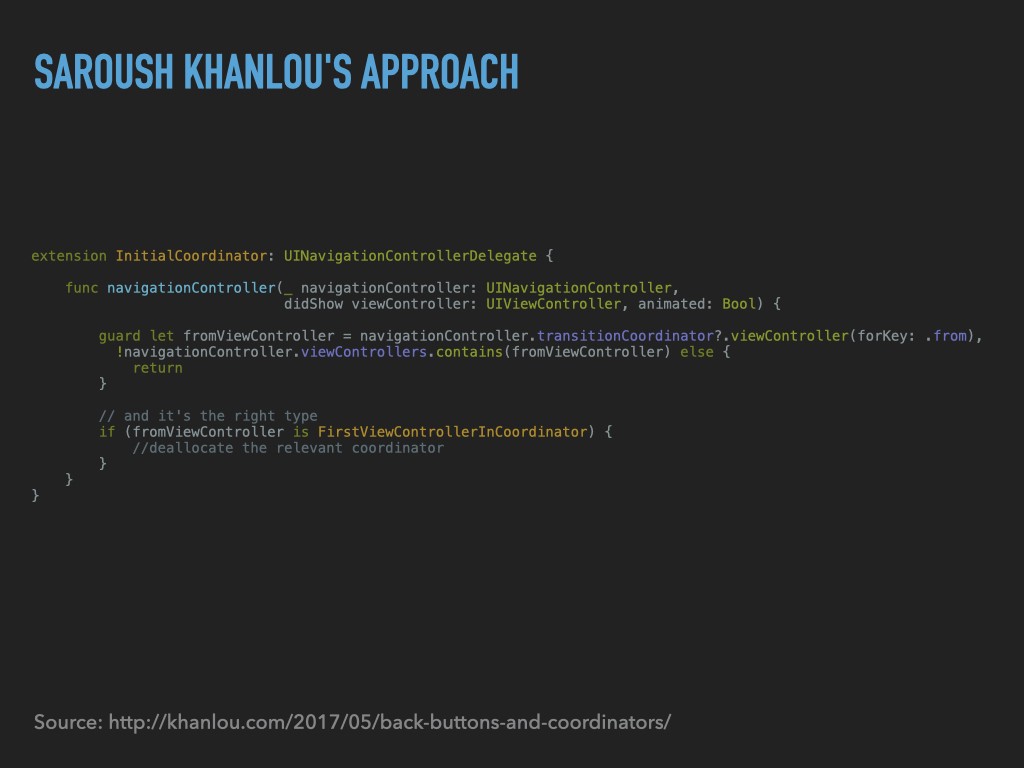

Soroush Khanlou.

One example is taken from Soroush Khanlou’s article on Advanced Coordinators.

It works, however in my view, it starts to steer away from the simple purpose of the coordinator.

It becomes the delegation for a navigation controller which means that it would override any previous implementation and cause that to stop working.

It also begins to include logic that isn’t immediately apparent what the purpose is.

This one method is called on both presentation and dismissal, it checks whether a specific view is contained within a retained collection of child coordinators, if so, it manually removes it from the store….all things that are ripe to cause the same memory issues that led us to this point.

Above all else, by making the coordinator the navigationControllerDelegate, you lose the interactive pop gesture, which is a damn shame.

Overall, it just didn’t sit right with me and I quickly began looking for alternative solutions.

Bryan Irace.

Here’s another approach by Bryan Irace.

In this, he’s taking the route of making a new controller object called a “NavigationController” (which I was easily confused with), that encapsulates both a coordinator and view controller.

It shares some DNA with Soroush Khanlou’s earlier method by having NavigationController be a UINavigationController delegate as well as the same method to specify which view or coordinator to deallocate.

I’d say it’s more complex than the previous approach, but it does encapsulate away some behaviour.

Ultimately, I wasn’t keen to implement this version of the coordinator either because it just didn’t align with what the concept of the Coordinator was in my head.

Tutorials #101.

There are tons of different articles and GitHub repo’s that cover this topic but none of them seemed to handle things in the way that I wanted — a light object and no requirement to manually deallocate anything.

One important thing to add here, and it is something to emphasis, is that none of the different approaches are wrong. They just didn’t seem to fit the way that I wanted it to work. I liked the concept, but couldn’t find an implementation that satisfied my….maybe I can call it “code lust”…no, actually that sounds sketchy. Let’s just say it didn’t satisfy my specific criteria.

So what did I do?

I Gave Up.

I stared listlessly out of the window looking for inspiration…

I took long walks trying to figure out:

“How can I cleanly remove a coordinator from memory?”.

I’m not the most interesting of people, it must be said.

But then I realised that we already had something available to us in the core iOS frameworks that managed both navigational flow and had the ability to let us know when objects were removed from memory.

UIKit is cool.

We have UIKit! It’s there, managing view hierarchies, throwing around objects, managing object retention and memory deallocation already. So let’s not fight against it.

Rather than coordinators retaining child coordinators, we make the initial view controller for a particular flow the “root view”, and that becomes the delegate of the coordinator.

The coordinator itself doesn’t have to change and we only need one root view for each coordinator flow.

What does this look like in practise?

In our use case, the coordinator will create the view controllers, but not retain them.

The new root view will hold a reference back to the coordinator and as long as that root view lives (as part of the UIKit view hierarchy), then so will the coordinator.

Other view controllers in the flow do not need to be coordinated. The coordinator is accessible via the root view controller for as long as it stays in memory. Of course, if there is an explicit need to reference a later view, you just need to have a weak reference to that specific controller.

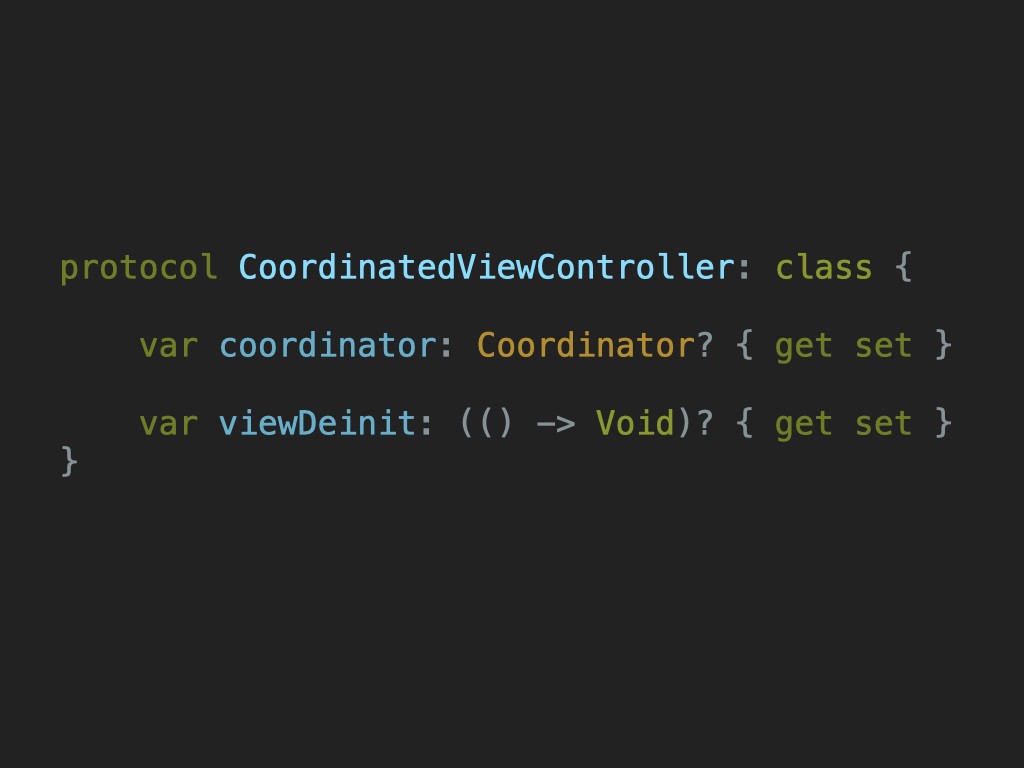

Protocols.

Let’s keep the original protocol, I like that bit, and add a little spice to it.

There’s a new protocol called CoordinatedViewController, which specifies just two properties.

The calling coordinator, the one that just created this view controller.

And a closure to be called when the view is deallocated.

For the situation where we have child coordinator flows, I’ve added a property to the Coordinator protocol called coordinatorFlowComplete, which is called to tell it’s parent that this particular flow is finished. The parent then can do any other logic/navigation/cleanup that it needs to do with that information.

Flow my views, the developer said.

And this is how it looks in operation — simple!

Going from left to right, we see that a coordinator creates a view controller.

The controller is retained by the view hierarchy, in this instance a UINavigationController, and the view retains the coordinator — our “Root View Controller”. As long as this root lives, so does the coordinator.

If the parent coordinator creates a child coordinator, the subsequent root retains that flow and so on…

We can add views/coordinators across the whole user journey and once we’re complete, walk back off the stack deallocating views and coordinators as we go. Once a root view controller deallocates, so does all of the coordinator resources along with him, all the way back to the parent.

Using this approach, there are a few things to note.

- The memory lifecycle is consistent with how we expect our UIKit apps to work. We don’t have to manually remove objects from retained objects, instead we just leverage our existing functions and observers.

- I’ve opted for protocol conformance rather than subclassing as that allows us to have a clearly defined “contract” with the specific view controller we want to become coordinated.

As I mentioned earlier, not all views in a flow need to be coordinated and in this instance they don’t need to implement this protocol. - Minimal code changes to existing coordinator implementations. Since all we have really done is flip the reference chain upside down, you can try this alongside your current approach. It also doesn’t require many changes to how view controllers are constructed.

- Most importantly of all, it doesn’t require the UINavigationControllerDelegate. Meaning I can still use the default interactive pop gesture.

What’s the point?

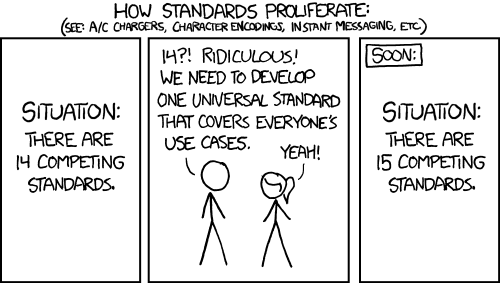

At the end of the day, all I’ve basically ended up with is yet another flavour of implementation on top of a giant stack of existing implementations. Why did I bother?

Sure, it shares some properties of a few different design patterns, but with one slight twist.

This one made sense to me.

And that’s the real theme of this article.

This is really about the bit in the middle — how did I get to the point of being able to reach down, grab my variation on a theme and add it to the rest of the other ways of doing things?

There are two key take aways I’d like to share on that point.

1. There is always another way.

Articles, blog posts, tweets or StackOverflow are incredible resources to have to help you find an approach to take. But they aren’t irrefutable.

We can read these other resources to give us an understanding of the problem we are trying to solve. And by understanding that problem, we’re able to come to our own conclusions and find a solution that works for the unique circumstances and requirements our project has.

It took me a long time to come to that solution, but having a grounding on how other people had attacked their problem enabled me to find something that fit my purpose.

Of course, this could also mean that the approach above may not work for you or your projects. But there may be some small element within there that nudges you one step further along your own journey to discovering the specific answer to your very unique questions.

2. Know what you want, not how to do it.

Early on in this voyage of self-loathing and regret, I knew that I wasn’t convinced by many other implementations of this pattern.

Even though I didn’t know how to do what I wanted, I had a clear idea of what I did want to happen, and what I didn’t want to happen.

I wanted to have navigation taken out of the view controller.

I didn’t want to have to manually deallocate objects.

I wanted to do as little work as possible.

And even though I struggled to achieve these goals, it helped me to throw away code and ideas when they didn’t satisfy my objective.

Written a class that doesn’t get deallocated? Throw the code away, try something else.

Coordinator becoming bloated? Throw the code away, try something else.

Protocol having too many properties? Throw the code away.

Because I knew how I wanted this thing to work in principle, I was able to check off against each of these requirements and if any part didn’t match up then I would bin it and walk away.

But on the flip side, when I was able to get an implementation that ticked all of those boxes, I knew that it worked.

In software development, the implementation is there to satisfy the behaviour that you want to occur.

I had to keep that in mind every time I tried to let existing code influence or constrain how I attained that behaviour, even if it meant putting everything in the bin.

Wrap Up

There you have it, this is what I presented once and may present again.

I hope there is something in this that you find useful, even if it’s only in knowing that there is at least one person working in a professional capacity that wasn’t able to grasp the concept of coordinators without losing their mind.

There is a demo of this project available on GitHub, please take a look and see what you think.

Maybe it won’t help, maybe it’ll make you laugh or maybe it’ll be a little pointer in helping you to find your own way of doing things and I look forward to seeing a different way to implement coordinators.

Demo project available at https://github.com/michaelsprindzuikate/coordinator_example